Mo Farah is an extraordinary athlete. During the

course of his career, he has won double gold medals in

the 5K and 10K races at the European Championships

the World Championships, and the Olympic Games.

When asked about his formula for success, he has a sim-

ple answer: “Training, you just have to put in the train-

ing”. In reality, of course, the success of an athlete like

Mo Farah is due to a wide variety of factors, including

natural ability, race strategy, preparation and execution.

Organizations, too, must balance different priori-

ties to compete; yet they face much more

uncertainty than an athlete like Mo Farah.

A race is a well-defined event. The loca-

tion, starting time, distance, competitors

and design of the track are all known in

advance. The “playing field” of business,

however, is becoming less clear.

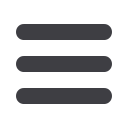

This lack of clarity is having a profound

impact on the effectiveness of traditional

strategies. Most strategy professors (myself

included) describe strategy as a cascade of

choices around where to play and how to

win. Good strategy is based on using solid

data and analysis to build an understanding

of your current position, figure out a desired

future position, and then design a plan to

get from here to there (see Figure 1). I firmly believe that

this model works. Or, at least it worked.

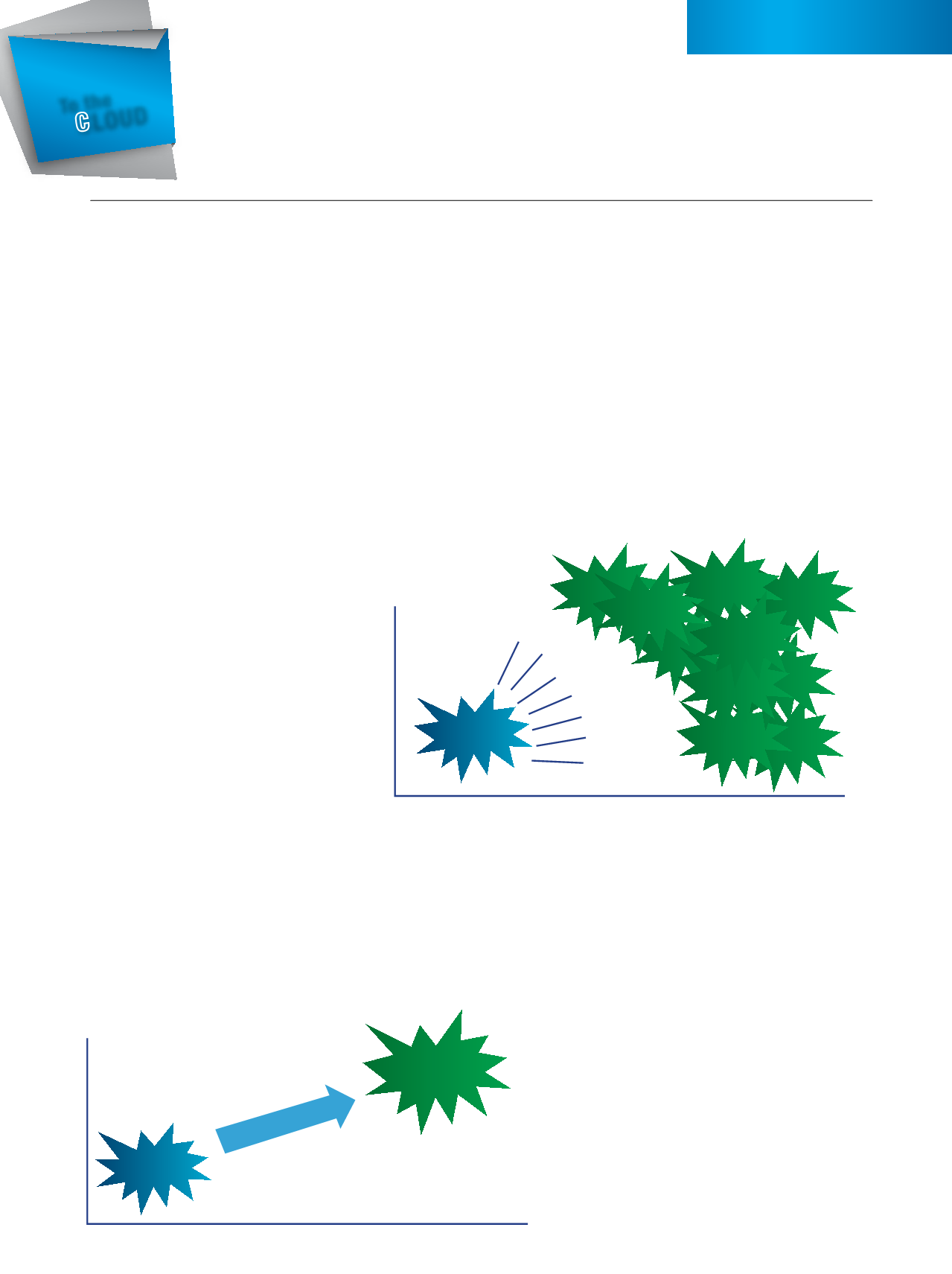

Today, I am no longer so sure, and for a very sim-

ple reason: the business world is changing so quickly

that predicting what the marketplace will look like

in the future is becoming increasingly difficult. How

many taxi companies incorporated the rise of Uber

into their strategic planning processes? And why is it

taking VW so long to react to its emissions crisis? In

a constantly changing world, a long-term strategy can

easily become an anchor that locks a company onto a

path that is no longer relevant.

The key elements for success today are not plans

and aspirations, but agility and capabilities. Capabilities

(or access to capabilities) are required to compete effec-

tively in a given position, and agility is required to make

shifts in that position in response to a changing environ-

ment (see Figure 2).

Coming back to our athlete: Mo Farah succeeds not

only because he is fast but also because he adapts to

the cadence of a race. He is a master of positioning, and

he sets himself up for a winning finish. Sometimes he

wins from the front, but more often than not, he comes

from behind to take the lead in the final lap.

Farah has phenomenal capabilities but limited agil-

ity. He may be able to adapt to the changing dynamics

of a race, but he would be completely lost if he

had to compete in the high jump, on a bicycle

or on a tennis court. A more extreme form of

agility is required by organizations as they move

to the center of the “digital vortex,” an environ-

ment characterized by high market turbulence

and shifting industry boundaries.

At the Global Center for Digital Business

Transformation, an IMD and Cisco initiative,

we define this extreme form of agility as digi-

tal business agility (DBA). DBA is composed

IP

Telephon

IP

Telephony

By

Professor

Michael Wade

The business world is changing fast, organizations have to adapt

ONETARY

To the

LOUD

ROFILE

on tary

louds

anaged

Services

anaged

Services

IP

Telephony

IP

Telephony

Here we

are

Let’s make a plan

Here’s

where we

want to be

The Traditional View of Strategy

Here we

are

Let’s make a plan

Here’s

where we

want to be

Here we

are

We can’t

predict the

future

????

????

????

????

Aglllty

The Traditional View of Stra egy

Emerging View of Strategy

Forget Strategy, Embrace Agility

70

Channel

Vision

|

January - February 2016