Contributed by Star2Star

From the wheel, the printing press, and the cotton gin to modern flight, personal computers, and artificial intelligence, technology is the engine that has always changed the world and moved us forward as humans. National Technology Day (January 6) is a day to recognize those achievements and to look to the future of technology.

Related: Celebrating National Telephone Day

For most businesses, technology is at the center of their strategic development. Whether it’s agriculture, healthcare, entertainment, food service, financial services, or another segment, technology is the linchpin for keeping us organized, connected, healthy, and safe.

One of the most effective tools for enabling growth objectives and the technologically savvy business of the future is Unified Communications (UC), which has grown from the simple idea of bringing voice and messaging platforms together into something much more advanced, cloud-native, and wide-ranging.

In Honor Of National Technology Day

To celebrate National Technology Day this year, here are five fun trivia facts that you may or may not know about phone technology and some of the parts that now make up today’s UC functionality:

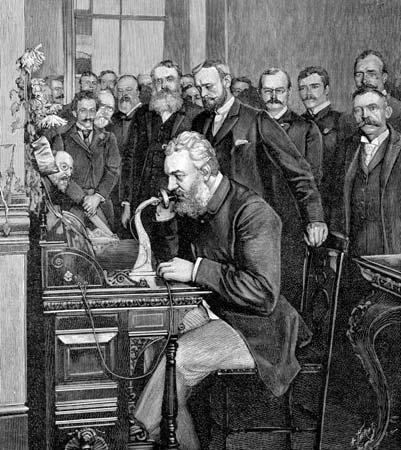

1) Calling Mr. Watson, What’s Your Emergency?

Alexander Graham Bell’s famous first call to his assistant, Thomas Watson, may have been the equivalent of a 911 emergency call.

Bell’s famous first telephonic words, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you,” were perhaps not uttered with the calmness that we assume. On the evening of March 10, 1876, Watson recalled, “I rushed down the hall … and found he had upset the acid of a battery over his clothes … his shout for help that night … doesn’t make as pretty a story as did the first sentence ‘What Hath God Wrought’ which Morse sent over his new telegraph … 30 years before, but it was an emergency call.”

However, many, including Watson’s great-granddaughter Susan Cheever, said that the acid story was an invention.

Speaking of controversy, the invention of the telephone was fraught with dispute, with Bell facing more than 500 lawsuits. The problem is that Bell was not the only one working on the concept. Elisha Gray, filed a caveat (a document saying he was going to file for a patent in three months) with the U.S. Patent Office at almost the same time that Bell filed his for a working prototype.

2) “Hello”?

“Hello” is a fabricated word.

Now that we had a telephone, we needed etiquette for using it, including how to greet callers. Bell always maintained that the proper telephone greeting should be a jaunty “ahoy.” Others clamored for a rather straightforward, “what is wanted?” or, perhaps, “are you there?” But it was Thomas Edison, the wizard of Menlo Park, that suggested the ubiquitous English-language greeting that we know today.

Allen Koenigsberg, a classics professor at Brooklyn College, found an unpublished letter in the American Telephone and Telegraph Company Archives in lower Manhattan, laying it all out. Dated Aug. 15, 1877, the letter was penned within the context of the phone being a device that had an open line at all times (hence the eventual role of the operator). Edison writes, “Friend David, I don’t think we shall need a call bell as Hello! can be heard 10 to 20 feet away. What do you think? EDISON.”

People liked it so much, it was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 1883.

“If you think about it,” Koenigsberg told the New York Times, “why didn’t Stanley say hello to Livingston? The word didn’t exist.” Hence, “Dr. Livingston, I presume.”

3) If The Phone Wasn’t Enough…

Bell also pioneered fiber optics.

After inventing the telephone, Bell founded Volta Laboratory in 1880, dedicated to the “increase and diffusion of knowledge relating to the deaf.” As part of this mission, he patented something called the photophone, which he dubbed the “greatest invention I have ever made, greater than the telephone.” It transmitted a wireless voice message by light beam–a precursor to fiber-optics, which didn’t come around in its present form until 100 years later.

4) A 1940s Cloud

The first “cloud-based” access to voicemail came in the 1940s.

In 1936, a company from Switzerland named Oerlikon pioneered something called the Ipsophon, which used magnetic steel tape to record messages. The size of a modern washing machine and containing a built-in handset for listening to a central repository of messages, it was strictly aimed at large enterprises. By the 1940s, the company had found a way to untether employees from the machine itself by allowing remote access from the telephone network. Users would whistle to activate the playback mechanism. The FCC gave the green light for the use of such answering machines on AT&T lines in 1949.

5) What’s Your Name?

Exchange names were a precursor to dial-by-name.

In the early days of telephone service, exchange names were used to help operators dial numbers. As some might remember, numbers on a telephone pad correspond to letters—an exchange is simply a word used to represent the first two letters of a seven-digit telephone number. For example, the exchange name “SYcamore” means that the first two numbers of the telephone number are “79”, and SYcamore-4-3317 would be 794-3317. So, callers would pick up a handset (it was still an open line, so an operator would come on automatically), and ask to be patched through using these names. Boring numbers eventually replaced the exchanges, but we’re seeing a reversal of the trend thanks to contact information being tied to individuals’ names in UC and mobile dialing conventions.

6) The World’s First Smartphone

Steve Jobs did not invent the smartphone.

While the advent of the iPhone in 2007 is credited with making the smartphone a “thing”, the world’s first smartphone debuted in 1993 at Florida’s Wireless World Conference.

Simon, launched by BellSouth Cellular, weighed a little more than a pound and offered an LCD touchscreen display and PDA functionality.

“Designed by IBM, Simon looks and acts like a cellular phone but offers much more than voice communications,” the press release said at the time. “In fact, users can employ Simon as a wireless machine, a pager, an electronic mail device, a calendar, an appointment scheduler, an address book, a calculator and a pen-based sketchpad — all at the suggested retail price of $899.”

Only 2,000 Simons were ever made. Perhaps the world just wasn’t ready.